By Analisa Price, originally posted on Femignarly on February 24, 2021

This one could get me in hot water, but I think it needs to be said. Women’s ski review coverage is a joke.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve written about how ski manufacturers are largely meeting women’s needs when it comes to their product lines, but how the sales aren’t what they could be due to the ways gender bias infiltrates the ski shop experience. But if women aren’t getting guidance from their local ski shop, where are they turning to? It turns out there aren’t great options, and today I want to talk about that info gap.

Now, before I delve any further, I work with a few ski content sites as a reviewer. I think the businesses I work with are doing the best job with women’s reviews and that partnership is the best way to improve resources for women. But no one is prioritizing women’s content enough, and women customers are paying for it, and I hope that this sort of criticism and dialogue are given credence.

But I also know that I’ve gotten some cringey responses when it comes to improving content for women. The one I think the most about? “Finally, I’ll leave you with this: there is no question that women are buying a ton of gear and equipment. Fact. But while that is true, it is not at all clear to me that many / most / a lot of women geek out on gear reviews the way that some guys do.”

So consider these my 95 Theses that I’m nailing to the door of the ski industry, both to brands and content creators, about how they must make the shopping experience better and fairer for women.

I’ll start with the number of reviewers. Most people see this as the source of the problem. I see it as an effect. If there’s not content that women find relevant, engaging, and educational, it’s almost impossible to graduate someone from a reader to writer.

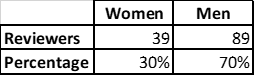

There are only a few sites who identify and profile their reviewers, which is really important since size and ability level influence your experience with a ski. Of the ones that do, here’s the breakdown in reviewer gender:

Other content sites that don’t explicitly share who their reviewers show a similar pattern. For example, Outdoor Gear Lab profiles 4 women testers who contributed to their women’s reviews, while their men’s reviews has a photo of 5 skiers that are captioned as “some” of the reviewers in their test. Switchback Travel’s Best All Mountain Ski roundup features reviews for 21 men’s models and 0 for women. Out of 37,560 words dedicated to the piece, they give us 182 words (under half a percent of the content) to tell us that sometimes women’s models are the same as men’s, but sometimes they’re softer or have more forward mount points and that we should demo and figure it out for ourselves. So if I had to guess how many women contributed to the piece, my guess would be under half a percent as well.

Less reviewers largely mean less content. I pulled 10 review sites for 2021 and counted the number of reviews for both men and women. Even though women’s skis make up 37% of the ski market, non-clearance sales, only 4 of the 6 ski content sites closely matched (within 2%) that gender breakout in their review content. And overall, only 28% of reviews were for women. Assuming that the number of models in production has remained consistent since 2019 (134 for women, 236 for men), the average women’s ski is covered in 2 reviews, and the average men’s gets 3 review pieces.

But this picture gets even worse. Not all reviews are good reviews. One of the women’s reviews I ran across was less than 100 words in length. In 100 words, it’s impossible to get a robust picture of how the skis handle in a variety of conditions, much less dive into the subtle nuanced differences between similar skis that compete against each other. So I pulled 3 reviews from each review site and took the word count to get a breakout of women’s content taking length into consideration. The percentage of women’s content shrinks down to 21% through this lens. Using the same model counts, the average women’s ski has 2,145 words of review content on these 10 sites, spread across 2 reviews (985 words each). And the average men’s ski has 4,627 words of content, spread across 3 reviews (1,440 words each). And this is operating under the assumption that these sites use the same word count across men’s and women’s reviews.

Anecdotally, some sites had higher word count and/or contributions from multiple reviewers of different sizes and ski styles for men’s review. I could easily see the ratio dipping below 20% content for women if I had the time to do a comprehensive text analysis for each review site and the average word counts across both genders.

Why it isn’t fair. One of the stats I shared in my last post on ski retail is that advanced to expert women and women shopping for skis over 100 at the waist are the least likely to shop in store. They aren’t able to leverage the expertise of retail staff, which means they need some other source of information to help them make decisions. This is where I really challenge the notion that women aren’t doing substantial research. What are the alternatives? Either she’s buying blind or just manifesting insights out of nothing to guide her purchases.

The good news is that we can largely see research. Google Trends allows us to see overall search tendencies, and I have the sales units for the 2018-2019 season. Google indexes their data, and I created an index for the sales units since it’s data I’m not supposed to have (shhh).

So I made the following chart. There’s a lot going on here. The first column is the indexed search history in Google Trends. The M5 Mantra was the most searched ski that season, with a search score of 21.5. The next column is the indexed sales data. The Black Pearl 88 and the Enforcer were the best selling skis in this set. The next column is my baby. It’s the search number, divided by the unit number, multiplied by 1000. The higher the number, the more searches were done per sale. Think of it this way: The Black Pearl 88 has a search score of 9.5 and the Santa Ana 100 has a search score of 8.4, so fairly similar. But the sales for the Black Pearl were 14 times higher than the sales of the Santa Ana 100. So I’m assuming that the Santa Ana 100 customer is doing more research in their ski selection, and that more Black Pearl 88 customers picked out the ski because of non-research factors (likely ski shop recommendations, advice from friends or partners, or based on factors like pricing or graphics).

I also added the percentage of sales done online for each model, since that’s also a good indicator of who needs non-retail advice and information.

So what does this mean for content creators? One of the things I found really interesting is that search velocity was too low to even register on Google trends for almost all skis narrower than the mid-80s, even though sales are often highest for beginner and lower intermediate skis. For example, the Black Pearl 78 outsells the Black Pearl 98, but the narrower version doesn’t hit Google’s velocity threshold. Most women start searching skis as they move into skis in the mid- to high 80s underfoot, and even amongst those, it tends to be the stronger models. If the bandwidth for women’s skis is limited, why do we have so much 5 reviews a piece for narrow Black Pearls and Astrals if they’re not the ones women are researching? We need to be way more strategic about the skis we’re reviewing and respective word counts we’re putting into them and ensure we’re offering enough information to women, progressing intermediate and above, to build a short demo list or be able to make an un-demoed purchase with relative confidence.

For another example, we’ve got the Blaze 94 W, which has 1 review and 700 words, despite the fact that it replaced the outgoing 90Eight W, which was a top 20 ski for women. Meanwhile, there’s over 3,000 words dedicated to the Hinterland Maul 121, an incredibly niche model from a small-batch manufacturer.

Oh, and note that the most heavily researched skis are women’s, and within this subset of skis, women’s skis were more heavily researched overall (with an average search-to-sales ratio of 5.1 vs. 3.9). I won’t argue that women are bigger gear nerds – there are lots of beginner skis that sell like hotcakes that don’t get searched – but I also think the data is strong enough not so readily perpetuate sexist generalizations that women are too simple or uninterested to really nerd out on gear.

See, most brands have shared shapes and materials across their gendered lines. In some cases, the skis end up quite different, like the Black Pearl 88 vs. the Brahma 88, but mostly they’re similar, and in a lot of cases, they’re the same exact ski with different sizes and graphics. However, brands are incredibly tight lipped with regards to the differences, and sometimes even use misleading marketing to create the illusion of difference. For example, my Ripstick 102 W in a 170 length is the same ski as the men’s Ripstick 106 in a 172. Or the Pandora and Sick Day are the same for the 94 and 104, but the product pages give the men’s a stiffer flex rating and suggest the women’s is softer, but it’s all smoke and mirrors.

We could feasibly write collaborative review content. If brands were transparent about when skis were the same or very subtle (minor changes in flex/mount point), a lot of the experience will be the same. Instead of writing thousands of words on her own experience, a woman can add to a unisex review about how similar/dissimilar her experience was vs a male reviewer and write a few comparison notes to other women’s models.

Likewise, those disclosures could at least let women glean more from a men’s ski review when there’s not coverage for women. I know I’m not the only girl who’s read through the reviews for men’s skis and then done their own detective work on mount points and weights trying to ballpark whether those comparisons hold true on the women’s side of the line.

And ladies, if you’ve ever spent two months reading ski reviews, felt zero direction, and ultimately called demo shops across 3 states to pay over $100 in rentals just to feel confident in your purchase, that is the quintessential female experience. I know a lot of women have sensed that they weren’t getting what they needed from review sites, but I hope seeing the data solidifies it and helps us advocate for more coverage. And lastly, if any of you aspire to write, everyone wants more women contributors and everyone is downright terrible at recruiting them. There’s no expert skill requirement – honestly, that can often hurt relatability. And I’d love to be a mentor along the way.